On a rainy summer day in Berlin-Neukölln I spoke with Moritz Gansen and Sara Morais dos Santos Bruss met for a ‘theory conversation’ loosely centered around the theme of the issue, General Public.

Read MoreSeason 3, Episode 5: Black Imagination

In the latest episode of the Decolonization in Action podcast, I spoke with Natasha Marin, curator of Black Imagination: Black Voices on Black Futures (2020, McSweeney’s).

Read MorePerennial Disasters in Port Cities

Here is my latest article in Verso Books which discusses the vulnerabilities that port cities have historically had along with a brief review of Laleh Khalili’s book Sinews of Trade.

Read MoreHow the myth of Black hyper-fertility harms us

The reproductive and sexual health of Black people living in the United States is dark and tied to the dark history of forced reproduction under slavery and forced sterilisation since post-emancipation.

Read MoreNew Queer Photography

If you are visually oriented, you might be interested in the book New Queer Photography edited by Benjamin Wolbergs which features a text I wrote on queer pageants in South African townships.

Read MoreThe Seeds of Revolution

While millions protested the murder of George Floyd and police brutality against Black people all over the world, there have been many voices criticizing the lack of acknowledgement of the injustices towards Black women, and of their leading roles in social justice movements

Read MoreIntersectionality in Data Studies

I wrote an article for Environmental History Now entitled Embracing Intersectionality in the Age of Bad Data. Here is the Text

——

Technology is an extension of societal mores and seeps into our lives, how we breathe, what we know, and how we move sometimes leaving an indelible digital mark. Since the rise of Covid-19, technology has played a major role in how we understand the progression of the disease, how we communicate with each other, and how our movement is now—suddenly—linked to an airborne disease. During a moment where computers, cellular phones, and online conferences can help support social distancing and minimize the risk of spreading the novel coronavirus, it is also important to think about the ways that digital technology—whether it be cameras, surveillance, and artificial intelligence software—do the work of what Lisa Nakamura terms “cybertyping.”[1] That is, the ways that the Internet disseminates and commodifies images through racialized technology. What we know is that technology has a deleterious impact on our data and the environment. However, it is worth unpacking the politics of data, privacy, and the environment from an intersectional lens, especially as we think of the invisibility and hypervisibility of marginalized groups.

Over the recent weeks, there have been ample debates about the politics of track and tracing apps, especially how they can potentially impose on people’s privacy. Some governments argue that accessing the movement of people could provide public health data that would spot clusters of infection for the novel coronavirus. In Europe, contact tracing apps have emerged as part of a broader public health policy to track the progression of Covid-19. Italy introduced its platform Immuni that began in mid-June, France has activated its StopCovid app, and Germany’s app (which is where I live) began its app Corona Warn app in June 2020.

While the General Data Protection Regulation guides data protection and privacy in the European Union and European Economic Area, one major issue is that the tracing apps open up a host of questions regarding the power of tech firms to accumulate and access people’s data. This has led some officials to say that the risk of privacy intrusion is not worth engaging in tracing apps. In Norway, officials halted the use of the Smittestopp app—created to combat the novel coronavirus—after the country’s data-protection authority raised alarms. The Norwegian government’s concern about the tracing app extends to the latest coronavirus virus and the processing of personal data. Yet the issue is much deeper than that.

Data privacy is an intersectional issue that should consider how marginalized groups are disproportionately targeted or harmed by data technologies. While Black people living in the United States are disproportionately infected and dying from Covid-19, very little is being done to provide. The consequences of contact tracing apps extend from the preexisting inequalities that get reproduced to the carbon footprint of the technology itself. This means it’s necessary to think deeply about the gender and racial absences in tech design. The reality of racist technology, as Ruha Benjamin outlines in her latest monograph, is a work of politics and sociology that explores how social relations, particularly of race and power, shape the digital landscape, by inquiring into the design practices of the tech industry. Borrowing from the legal scholar Michelle Alexander, Benjamin argues that we live in a new era, a space where the data divide manifests as “the New Jim Code.”[2] Blackness, in some cases, is made hypervisible especially in a moment when activists are fighting for their lives.

Unfortunately, the concerns about data privacy does not just impact African Americans, other groups are affected too. As the Washington Post reported in 2019, companies such as Palantir has been criticized for using the data that it collected to help health agencies to also find and remove undocumented people. Journalists have also expressed caution that contract tracing apps could inadvertently exacerbate the privacy of domestic abuse survivors if contact details were sent to their perpetrators.

An intersectional approach to data technologies would try to unpack how these data are biased in their outcome, but also, how they are biased by design. As Caroline Criado Perez noted, “[t]he gender data gap isn’t just about silence. These silences, these gaps, have consequences.”[3] What Criado Perez points to is how coding structures neglect women and make them invisible. However, one should go even further and point out that the gender binary and cis-gender centrism ignores the concerns of gender non-binary and transgender people. As Britt Rusert’s Fugitive Science shows, there is a long history of Black scientists, scholars, and artists resisting and subverting racist science. In the twenty-first century, racism is a classification practice that bears new life in technology.

One area that is often left out of the conversation on data studies is the way that it impacts the environment. Indeed, we should be concerned about the relationship between digital technologies and surveillance. At the same time, it is worth noting the ways that the tools we use—from cellular phones to data centers—create a deleterious impact on the environment. As Greenpeace reported, smartphones and data centers are harming the environment since they are one of the many mechanisms that impose a carbon footprint. The phones themselves produce little energy but their production will have long-term environmental impacts.

As media scholar Athina Karatzogianni noted, critical digital activism plays a pivotal role in generating social movements from below. A right to privacy is one we should all have, one we can effectively shape and collectively demand. Data for Black Lives, a non-profit organization, has been doing phenomenal work on how data needs to move from unaccountable racist policies towards one rooted in collective action.

Over the past few months, the world has come to know more about the life of the novel coronavirus—not something that is merely framed as the common flu, but more. We have to reckon with the global impact of the disease and the extent that healthcare workers and medical institutions can provide treatment. In situations where providers have limited resources or depending how the pandemic materializes in the Global South, a comprehensive solution based on mutual aid, material assistance, and universal healthcare will have to emerge. As Vijay Prishad remarked in February 2020, this is a time for solidarity, not stigma. That means we need to be critical of the surveillance laws that continue to devastate the lives of women, people of color, and people from the Global South.

[1] Lisa Nakamura, Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002).

[2] Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools Fo for the New Jim Code (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2019), 48.

[3] Caroline Criado Perez, Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (London: Chatto & Windus, 2019), xi.

*Cover Image Description: Street-level poster advertising on a street light, one reading BIG DATA IS WATCHING YOU.

Collective Grief

In slave times the Negro was kept subservient and submissive by the frequency and severity of the scourging, but, with freedom, a new system of intimidation came into vogue; the Negro was not only whipped and scourged; he was killed."

-Ida B. Wells

Last Monday, George Floyd, an African American man from Minneapolis begged for his life while police officer Derek Chauvin pinned him to the pavement with his knee on Floyd's neck. George pleaded "I cannot breathe," while handcuffed. Onlookers demanded Chauvin relent, but he continued to suffocate Floyd. A devastating, ten-minute video recorded the murder of George Floyd by Derek Chauvin. The video is damning and its reveals that Chauvin murdered Floyd. Black people are angered and grieving all over the world. Unfortunately, Floyd is not the only one we mourn. We grieve for Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Ahmaud Arbery, Steven Demarco Taylor, and so many more.

Black liberation struggle is ongoing and while many of us have a target on our backs, there is a rich history of insurrection that shows that we will not die lying down.

The recent set of events, are part of centuries long struggle for Black freedom in a society that has enslaved, imprisoned, and killed Black people. This echoes James Baldwin’s dismay of the United States, that somehow “the American tragedy has always been implicit—was to make black people despise themselves.” The adversities is present but so is our collective struggle to document and destroy the chains of oppression.

The African American journalist, Ida B.Wells (1862-1931) was honored with the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in the Special Citations and Awards category for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching. After three of her friends were lynched in Memphis, Wells set out to investigate white mob violence and lynching across the American South. Wells is widely regarded as a fearless leader and reporter who shined a light on lynching, even as she faced racism and sexism herself as a Black woman.

This is particularly noteworthy given that the New York Times Black American journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones was also awarded a 2020 Pulitzer Prize for her writing on and ongoing work focusing on racial injustice. In 2016, Hannah-Jones co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting. The goal was to raise awareness of, and opportunities for, investigative reporting by journalists of color and to foster the desire for social justice journalism and accountability reporting about racial justice. One noteable aspect of her work has been finding the 1619 Project which looks at the impact of slavery over 400 years.

In contemporary left political discourse, race is often pitted against class, causing a huge rift within social movements. Yet, some scholars pursue another direction, hoping to use scholarship for transformative justice that shows how these categories intersect. In a recent short documentary entitled "Geographies of Racial Capitalism," Professor Ruthie Gilmore explains how capitalism relies on racial inequality to survive. She also goes into depth about the international context of her research which seeks to understand how capitalism relies on the criminal injustice system to further its goals. What does she think we should do: abolish prisons.

The Imperial Machine Behind the Cholera Epidemic in Yemen

This is my latest contribution to Science for the People Magazine, a publication that aims to understand the history and political trajectory of science practices. If you’re interested in my take on imperialism’s relationship to epidemics you might want to read this text which you can find here and the full transcript below.

From Science for the People

Volume 22, number 2, Envisioning and Enacting the Science We Need

Since the Saudi Arabia-led war against Yemen began in 2015, two million people have been displaced and over ninety thousand have been reported dead as of June 2019.1 The war has also created the conditions for a horrific and sustained cholera outbreak.

Yemeni and non-Yemeni scientists and government officials have analyzed the cholera outbreak on a genetic and public health level, and researchers at the Pasteur Institute surmise that the cholera epidemic in Yemen is related to a broader, global pandemic, associated with the bacterial strain known as 7PET.2 Scientists from the Los Alamos National Laboratory have indicated that the cholera strain in Yemen is particularly virulent and resistant to most antibiotics.3

The morass of details uncovered in these studies about the disease’s genetic traits, bacterial properties, and treatment leave hidden the origins of this illness in war and imperialism. By misconceiving it as an infectious disease pure and simple, these studies focus on the incidental features of cholera rather than the political and social causes germane to its eradication. Once the social and material roots of the illness are taken seriously, the path to eradicating cholera becomes more clear. This is a public health emergency that can only be addressed by focusing on both the infectious bacterial disease aspect of the illness and by bringing the war itself to an end. In the meantime, it is essential to direct resources to rebuilding infrastructure and revitalizing local and community-based medicine.

In Yemen, the cause and trajectory of the recent cholera epidemic cannot be reduced to its genetic characteristics or be solved by foreign humanitarian aid or antibiotics alone. Rather, one must critically examine the social and material conditions conducive to the production and spread of infectious disease. The circumstances that create modern epidemics cannot be extricated from their financial or imperialist roots. Imperialism has a lasting political imprint even when territorial colonialism no longer exists. Yemen has been a laboratory for financial imperialism, steered by foreign capital through high-interest loans at the behest of domestic rulers. Epidemics, such as the current cholera outbreak in Yemen, are a direct consequence of modern-day imperialism that produces new outbreaks and new tragedies. Yemen is a perfect case study for understanding how imperialism makes people sick.

Today, covert imperialism and overt military intervention create the conditions for the cholera epidemic to emerge and flourish. The 2015 Saudi Arabian invasion of Yemen, along with a preexisting poor sanitation system, made it difficult for the Yemeni government or international organizations to manage the outbreak of cholera the following year. The Yemen Data Project has documented that the Saudi Arabia-led war has resulted in over twenty thousand coalition air raids on Yemeni people since 2015, damaging hospitals, roadways, and cultural sites.4 Researchers estimate that by the end of 2019, 133,000 people in Yemen will have died from the conflict and another 233,000 from conflict-related symptoms, including pervasive hunger and ill health.5

Although international organizations and foreign governments have donated millions of dollars to address the cholera epidemic in Yemen, these public health interventions have been unavailing, at times “pitting one approach against another,” as Louise C. Ivers, executive director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health, indicated.6 Shireen Al-Adeimi, Michigan State University Professor of Education, argues, “Saudi Arabia has an interest in maintaining control over Yemen,” which is part of an ongoing imperialist relationship.7 Since 2018, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have donated $145 million (USD) and the United States has given $20 million to the World Health Organization to provide health services to Yemen.8 While these entities profess to reduce cholera’s presence, the United States and Saudi Arabia are directly involved in producing the conditions for disease proliferation through the war. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States governments have distributed funds for public health relief in Yemen, yet they have not taken the decisive step to end the war. Peace and self-governance are prerequisites for the Yemeni people to end the cholera epidemic.

With the end of European colonialism, imperialism is now shaped by international corporations and power players on all continents. Given this dynamic, we must also consider multifarious decolonial strategies in medicine and public health in solidarity with civilians and the victims of war, especially when medical infrastructure is subjected to destruction. Internationally coordinated militarization perpetuates mass death, while humanitarian aid is governed by Saudi Arabia, the US, and other world powers. As it currently stands, international financial regimes and non-governmental organizations, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), produce uneven financial relationships in Yemen—accentuating poverty and illness.

An anticolonial approach to the history of disease can be traced to the mid-twentieth century when Frantz Fanon, author, doctor, and political philosopher, eloquently remarked on the convergence and hierarchy of life and death. He wrote, “With medicine we come to one of the most tragic features of the colonial situation.”9 As a psychiatrist, Fanon was mostly studying the sociodiagnostics of racial tensions between Black and white people, but saw that a similar tension played out in the treatment of the colonized in Algeria. Fanon’s proximity to French colonial violence, his training in medicine, and his participation in Algeria’s struggle for independence gave him singular insights. His position as a medical practitioner within the French colonial regime was the fuel that sparked his anti-colonialism. His analysis of medicine under colonization, developed during the Algerian War of Independence, led him to conclude that Algerians were pathologized under times of war.10

A reading of Fanon and other anti-colonial writers can deepen our understanding of psychiatric illnesses. However, I argue that they can be extended to other diseases, especially in the contemporary context. Understanding the intersection between disease and imperialism today can also help to show how we might begin to rectify the conditions that subject people to epidemics and disasters. At the core of Fanon’s essay, “Medicine and Colonialism,” was a deep meditation on the relationship between medicine and colonialism, in which colonial power could be exercised not just materially and physically over people and objects but also through ideology.11 Studying the causes of disease through the lens of neocolonialism helps us see how disaster and death happen under purportedly humanitarian intervention. Such is the case in Yemen.

Perennial Imperialism

…To appreciate the extent to which Yemen’s story is ‘complicated’ requires moving beyond the geographies, historiographies, and epistemologies used to make Yemen conveniently legible to specialists.12

—Isa Blumi

For most of the twentieth century, Yemen was divided into sultanates, with local rulers directing their allegiance to fit their will. As early as 1958, the imamate in northern Yemen looked to the Pan-Arabism of Gamal Abdel Nasser, which eventually led to the formation of the Yemen Arab Republic. In the south, British colonial rule had established Aden as a protectorate in the nineteenth century and functioned as an integral part of Red Sea trade. With armed struggle and a desire to form an Arab socialist state, the People’s Republic of South Yemen, later the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, broke free from British tutelage by 1967. However, the civil war led to political instability and also the forced displacement of Yemeni people.13 Similar to East and West Germany, unification of Yemen occurred shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in May 1990.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union led to Ali Abdullah Saleh, the then leader of North Yemen, becoming president of the United Republic and Ali Salem al-Beedh, former Secretary General of the Yemeni Social Party, becoming vice president. However, the country could not recover from what preceded during the period of conflict, and poverty contributed to incessant and incremental emigration. Yemen’s pacts with its oil-rich neighbors dictate the extent to which Yemenis may live and work in those countries, with Yemenis often providing cheap labor to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states.

In 1990, when the United States government proposed its plan to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to invade Iraq, the Republic of Yemen voted against the invasion. The consequences of denouncing the war in Iraq came with a temporary halt in aid and remittances, which crippled the economy. The GCC countries discontinued $500 million (USD) in foreign aid to Yemen.14 As Saudi Arabia is a member of the GCC, 800,000 Yemenis, most of whom had been residing in Saudi Arabia, were expelled from GCC countries.

The government of Yemen became further indebted through privatization programs that it implemented through the World Bank and the IMF. According to Isa Blumi, privatization led the Yemeni government to open up its economy to the free market, which eventually resulted in the liberalization of the “banking, agricultural, and oil sectors.”15 Another dimension was reviving economic investment and collecting revenue from international traders in the port of Aden, which began under President Saleh, by creating partnerships with the International Dubai Seaport Company in 2008.16 Saleh’s financial ventures did not end there.

A mix of corporate and multilateral aid from world powers is inconsistent in its perspective and policies: it creates financial crises in Global South countries while subsequently forming charity-like relationships through humanitarian aid. Multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF, as Walden Bello has noted in his book, Deglobalization, sidestep democracy by usurping a significant amount of decision-making power.17 In the process of creating uneven financial systems, total war, and aid-dependent societies, new forms of imperialism are created. It is in this vein that decolonial strategies can begin to undo the damage and shock to postcolonial states. As early as the 1990s, Saleh requested loans from the IMF and World Bank as part of a slow process of financial reconfiguration and massive structural adjustment programs. Yet, money was not the only reason Yemen became beholden to foreign interests. A turning point in the Republic of Yemen was September 11, 2001. During that political moment, Saleh acquiesced to supporting the US invasion in Iraq and allowing US Military Special Forces to have a presence in the country. In exchange, he acquired American weaponry, which was used for internal disputes. For example, in August 2009, Saleh launched Operation Scorched Earth, with the help of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, to attack Houthi rebels.18

The military assaults in the early 2000s, alongside economic distress and authoritarian rule, were some of the many reasons leading to the 2010-2011 Arab Spring uprisings. After various protests in Karama Square in the Yemeni capital of Sana’a and throughout the country, President Saleh pledged not to extend his rule. However, his offer was to pass on the presidency to his son, which led to months of protests. By November 2011, President Saleh finally agreed to remove himself from power and hand the affairs to his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, which led to a general election won by Hadi. But in 2014, Houthi rebels rose to power in northern Yemen and rejected a draft constitution proposed by the government. By the end of the year, they took control over a significant portion of Sana’a. The Houthis have received funds from Iran, and since Iran and Saudi Arabia are in conflict, this supports the idea that Yemen was a pawn in international relations over which they may have little or no control. At the same time, the Houthis have recently evolved independent of Iranian directives.19

In August 2018, a Saudi-led airstrike (with a US-supplied bomb) hit a school bus, killing fifty-one people, including forty children.20 While the assault targeted rebels, it was innocent civilians who suffered because of the destruction. Fourteen million people—half the population of Yemen—are on the brink of starvation.21

Imperial Cholera

The human cost of the Saudi-led conflict in Yemen today is grave and growing. The war has created conditions of increasing malnutrition and, therefore, compromised immune systems susceptible to infectious disease. War-induced displacement has created an internal refugee crisis, while basic infrastructure, such as sanitation, is being decimated. Collectively, these conditions are ideal for the spread of cholera. Like a prodigious avalanche gaining strength as it rolls down a mountain, cholera is spreading throughout the country and getting out of control.22 Moreover, the pressures of financial deficit and environmental disaster have weakened the very institutions capable of tackling this twenty-first century horror.

The horrific loss of life, widespread malnutrition, displacement, massive destruction of public infrastructure, and the out-of-control cholera epidemic have led to denouncement of the war in Yemen for humanitarian reasons.23 While, in principle, treatment of cholera only demands providing clean water, oral rehydration salts, and gloves, the conditions of war in Yemen are such that these interventions are neither possible nor effective. In 2017, Raslan et al. write in Frontiers in Public Health:

A failing sewage system, continued conflict and inadequate health care facilities are only a few of the reasons contributing to this problem. Malnutrition, which is a significant consequence of the Yemen War, has further contributed to this outbreak.24

A sense of the scale of the crisis can be gleaned from the reports of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which reports treatment of 103,000 individuals in thirty-seven locations since 2015. Since 2018, they have incorporated seventeen treatment centers with supplies including IV fluids, oral rehydration supplies, antibiotics, chlorine tablets and sent engineers to help restore water distribution across Yemen. However, MSF, like millions of Yemeni people, have also faced direct military attack. Since 2015, Saudi airstrikes have targeted MSF treatment centers, despite receiving the centers’ GPS coordinates in order to be spared.25

In May 2018, MSF launched an oral cholera vaccine campaign in Yemen and attempted to deliver medication to 540,000 Yemenis, though they were only able to distribute the materials to 387,000 people.26 While these efforts have been well received and provided some relief, the outbreak continues. Federspiel and Ali wrote in the BioMed Central Public Health:

Whatever the reasons, OCVs [oral cholera vaccines] were not distributed until nearly 16 months into the cholera outbreak by which time more than a million cases had accumulated … This should serve as a historic example of the failure to control the spread of cholera given the tools that are available.

Non-governmental organizations are not the only ones trying to stem the outbreak. The Yemeni government has also contributed, albeit under the strain of financial restrictions. Over the past few years the Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen has struggled to provide adequate services, leading them to partner with the World Health Organization to deliver widespread vaccinations.27 Despite these international efforts, fewer than half of the hospitals in Yemen are operational, suffering shortages of staff and supplies due to the ongoing conflict.28 The thirty thousand doctors, nurses, and other health care workers of Yemen worked for months without pay. These catastrophic conditions are a consequence of this modern-day war, where massive military operations have not only resulted in infrastructure destruction but also the decimation of the body politic.

Unpacking the Theory and Practice of Decolonization

This collective memory of imperialism has been perpetuated through the ways in which knowledge about indigenous people were collected, classified, and then represented in various ways back to the rest, and then through the eyes of the West, back to those who have been colonized.29

—Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies

Yemeni people are subjected to militarized violence— a product of uneven neocolonial power relationships. An underappreciated fact of the cholera epidemic is that the people of Yemen are maligned by a political ideology that attributes the conditions of poverty, illness, and even natural disasters to the failure of the people themselves, rather than recognizing that their roots lie in the structures of neocolonial and imperialist interventions that have either created or aggravated the present-day disaster. While the UN has said that the war in Yemen has caused “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis,” liberal commentators attribute the disaster in Yemen to intra-Yemen disputes, Saudi intervention, and Houthi rebels without breaching more deeply into the role of imperial powers who simultaneously fund and participate in the war and act as humanitarian saviors.30

An Anti-Colonial Perspective

Multilateral agencies with unilateral power, such as the World Health Organization, and foreign governments that have used military force in Yemen, such as the United States, will not solve the humanitarian crisis through charity.31 Instead, it is important that Yemenis gain and exercise political independence as an act of decolonization and remove the power structures that created the catastrophe. This is where political self-determination and anti-colonial perspectives can be useful in generating genuine change. As ideology, decolonization can help to cohere a broader layer of political subjects that are left outside of mainstream politics. In Fanon’s analysis of the struggle against French colonialism in Algeria, he outlined the growing recognition in the liberation movement of the need to include a working class; Algerian representation was required to challenge the military occupation. Scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang offer fresh insight on how to remove modern imperial legacies in their essay, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” stating, “Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools.”32 In the case of Yemen, that would mean severing the politically capricious situation where countries such as Saudi Arabia both exercise military force and provide humanitarian aid. We need new options to treat the cholera epidemic today that do not rely on these imperialist powers.

Decolonizing medicine would require reformulating the ways that disease categories get defined, how treatments are enacted, and who is considered a healer. Expanding the categories and actors who are abating disease could also mean incorporating traditional healers from Yemen who could not only serve as bearers of local knowledge but also as medical experts for the region. Outside of Yemen, there are interesting programs that explore horizontal and justice-oriented frameworks for healing, including Dr. Rupa Marya’s “Do No Harm Coalitions,” that believe that health is a human right and strive to incorporate collective social justice in their approach while training a new generation of medical students to think about power and privilege.33 A British collective, Decolonising Contraception, has found ways to destigmatize reproductive health through workshops. These initiatives provide examples of non-judgmental, progressive, and patient-oriented approaches that Yemenis could draw from when rebuilding their medicinal infrastructure.

A harm reduction practice that addresses the cholera epidemic in Yemen might benefit from theoretical frameworks that explore politics from a feminist and materialist perspective. Feminist scholars have argued that horizontal, reflective organizing is a necessary mental framework of decolonial processes. As Sara Ahmed remarks, “Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground.”34 One prime example of solidarity is providing material support, as the sociologist Alondra Nelson reflected, which ranges from reconciliation to reparations.35 Reparations can include targeting institutions, businesses, associations, and governments that have plundered and profited from formerly colonized and enslaved people, and therefore poses questions about where wealth comes from and how to redistribute materials in a democratic fashion. For Yemen, that would mean interrogating its proximity and relationship to the United States, Saudi Arabia, and undemocratic unilateral agencies.

In Yemen, the current social and political order of war deepens the fault line of inequality. A decolonization perspective allows us to understand the health crises in ways that are not narrowly conceived as purely medical. Decolonizing the practice of medicine would require the expansion of methods that give due regard to the politics and history of Yemen. In People’s Science, Ruha Benjamin writes that if one can acknowledge and upend health inequalities, people can begin to have the space and time to be more creative as they move through the world.36 To decolonize medicine in Yemen would mean empowering Yemeni medical practitioners while challenging the imperialist and neoliberal legacies and current practices that influence biomedicine and lie behind the health crisis. The non-governmental organization industrial complex, as perpetuated by the World Health Organization and the UN military forces, are part of the problematic regimes that should be challenged.

Decolonization can help challenge the neocolonial and imperialist interventions in Yemen in material ways; it is not merely a matter of atonement but reimagination, something that was rife during the anti-colonial movements in the mid-twentieth century. As a revolutionary, Fanon offered a praxis for liberation and solidarity in colonial contexts. In a broad sense, he also believed that decolonial practices were not merely about creating new political bureaucracies but incorporating health more fundamentally. Colonialism creates new pathologies, and under conditions of duress, colonized subjects are made sick. It is in this respect that decolonization brings to light new approaches to understanding illnesses and how we might go about curing them.

About the Author

edna is an anti-colonial activist, herstorian, writer, curator, and educator whose work interrogates disease, gender, surveillance, and embodiment. edna earned a PhD in history of science at Princeton University with a dissertation that explored plagued bodies and spaces in North Africa. edna’s work is guided by diasporic futurisms, herbal healing, and bionic beings.

References

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project and Yemen Data Project, “Yemen War Death Toll Exceeds 90,000 According to New ACLED Data for 2015,” Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019, June 18, 2019.

François-Xavier Weill, Daryl Domman, Elisabeth Njamkepo, Abdullrahman A. Almesbahi, Mona Naji, Samar Saeed Nasher, et al., ”Genomic insights into the 2016–2017 cholera epidemic in Yemen,” Nature 565 (January 2019): 230-233.

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, “Mystery of cholera epidemic solved,” Science Daily, January 2, 2019.

See the Yemen Data Project, yemendataproject.org, last accessed October 18, 2019.

Jonathan D. Moyer, David Bohl, Taylor Hanna, Brendan R. Mapes, Mickey Rafa, “Assessing the impact of war on development in Yemen,” (Sana’a, Yemen: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019).

Louise C. Ivers, “Vaccines plus water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions in the fight against cholera,” The Lancet Global Health 5, no. 4 (April 2017): e395.

Chris Gelardi, “War Crimes in Our Name: A Q&A With Shireen Al- Adeimi,” The Nation, December 14, 2018.

“Donations from Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates provide access to health care for millions in Yemen,” World Health Organization, accessed July 31, 2019.

Frantz Fanon, L’an Cinq De La Révolution Algérienne [A Dying Colonialism] (New York: Grove Press, 1967 [1959]), 121.

Fanon spends a considerable time in the section on violence discussing the ways that colonialism “dehumanizes the colonized subject” (p. 7) and how the colonialist speaks of the colonized in zoological terms which allude to bodily compartments and diseases. Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [Damnés de la terre] (New York: Grove Press, 2004 [1961]), 7.

Frantz Fanon, “Medicine and Colonialism” in A Dying Colonialism, (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 121-145.

Isa Blumi, Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia Tells us About the World (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018), 8.

Fred Halliday, “Catastrophe in Yemen,” Middle East Research and Information Project 139 (March/April 1986).

Nora Colton,“The Silent Victims: Yemeni Migrants Return Home,” Oxford International Review 3, no. 1 (1991): 23–37.

Isa Blumi, Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia Tells us about the World (University of California, 2018), 190.

Blumi, Destroying Yemen, 178–179.

Walden Bello, Deglobalization: Ideas for a New World Economy (London: Zed Books, 2002).

Caryle Murphy, “Analysis: What is behind Saudi’s offensive of Yemen?” Public Radio International, November 2009.

Vincent Dirac, “Yemen’s Houthis–and why they’re not simply a proxy of Iran,” The Conversation, September 19, 2019.

Julian Borger, “US supplied bomb that killed 40 children on Yemen school bus,” The Guardian, August 19, 2018.

“Yemen: Houthis launch drone attacks on Saudi airports, airbase,” Al Jazeera, August 5, 2019.

Jonathan Kennedy, Andrew Harmer, and David McCoy, “The political determinants of the cholera outbreak in Yemen,” The Lancet Global Health 5, no. 10 (October 2017).

See: Tawakkol Karman, “Enough is Enough. End the War in Yemen,” Washington Post, November 21, 2018; Jeffrey Feltman, “The Only Way to End the War in Yemen,” Foreign Affairs, November 26, 2018; Martin Griffiths, “The Secret of Yemen’s War? We Can End It,” The New York Times, September 19, 2019.

Raslan et al., ”Re-Emerging Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in War- Affected Peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean Region—An Update,” Frontiers in Public Health 5 (October 25, 2017): Article 283.

“Unacceptable investigation findings into Abs health centre bombing,” Médecins Sans Frontières, February 6, 2019, msf.org.

Frederik Federspiel and Mohammad Ali, “The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and way forward,” BMC Public Health 18 (December 4, 2018): Article 1338.

“Health Crisis in Yemen,” International Committee of the Red Cross, March 6, 2019.

Shuaib Almosawa, Ben Hubbard, and Troy Griggs, “It’s a Slow Death’: The World’s Humanitarian Crisis,” The New York Times, August 23, 2017; Charbel El Bcheraoui, Aisha O. Jumaan, Michael L. Collison, Farah Daoud, and Ali H. Mokdad, “Health in Yemen: losing ground in war time,” Global Health 14 (April 25, 2018): Article 42.

Linda Tuhiwai, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2017), 1-2.

Krishnadev Calamur, “The Next Disaster in Yemen“ The Atlantic, June 13, 2018.

See Yemen Financial Tracking 2019, fts.unocha.org/countries/248/recipients/2019.

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 no. 1 (2012): 1-40.

Rupa Marya, “Decolonizing Medicine for Healthcare that Serves All,” Bioneers Conference: Uprising!, Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart, 2017; For information on Do No Harm refer to donoharmcoalition.org

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

Alondra Nelson, The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome (Boston: Beacon Press, 2016).

Ruha Benjamin, People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013).

An Intimate Black Space

My latest article in Griot Mag.

2 in 1 Salon, Joe Slovo Park, Cape Town, South Africa – via Wikimedia commons

“Where are you from?” I am often arrested or annoyed by this question. However, I was in Durban, South Africa and since this query was posed by a Black woman, I politely answered. “I’m from the United States and I live in Germany.” I stood at the entrance of a nearly empty Black hair salon, where the woodwind percussion of the South African artist Sjava blasted through the speakers. Before me were 5 Black women and one customer. I was wearing a black jacket, a black turtleneck, and high-waisted bleached stained jeans. I gazed sternly at the women, with the expectation that I would enter this portal for my beauty regime and manage the dwarfish Afro that lay close to my scalp. They looked dubious and increasingly became curious about my accent, my outfit, and my septum piercing. So as they suspected, I must be a stranger.At first, no one wanted to braid my hair. One person remarked, It’s too short. Another concurred, it will be difficult to grab your hair for the braid. To my chagrin, I made the case that I wanted a fresh look for the New Year, as a traveler from across the street, I wanted to support Black women in their craft. After some negotiation between the staff in English, Sara began to braid my hair. The other four continued texting on their phones, chatting and dancing to Afrobeats.

The contours of segregation in South Africa look different today, and on my journey, I began to unravel its complicated and coded layers.

The tragedy of the South African post-apartheid state is that space, land, and resources are highly divided along racial and gendered lines. In Durban, it was shocking to see how segregated public spaces were. On a sunny day, while walking along the beach, my partner and I found ourselves only among Black, South Asian descended and other people of color. At the pier, we watched the container ships go by, lovers taking selfies, and young children riding their bicycles. Other than my partner, no white people were occupying this public space. We wondered, where all the white people were until we passed by a yacht club, with its “members only” sign, and bore witness to this seaside white flight 100 meters from the pier. The contours of segregation in South Africa look different today, and on my journey, I began to unravel its complicated and coded layers.

Sign in Durban that states the beach is for whites only under section 37 of the Durban beach by-laws. The languages are English, Afrikaans and Zulu, the language of the black population group in the Durban area (1989), via wikimedia commons

Nevertheless, Black women gather in their own intimate spaces—in kitchens and salons. From Inua Ellams’s Barbershop chronicles to the gaudy rendition of Black salons by Tyler Perry, Black grooming spaces function as collective sanctuaries. On the surface of it, femme centered Black salons might seem like a counterpoint to the male-dominated barbershop–a socially raunchy space where people reassess their hopes and dreams. It is not. The Black hair salon is one of the few intimate spaces demarcated for Black women, Black queers, and Black gender non-binary people. Our beauticians create a chamber to breathe better.

For the first 30 minutes, I sat in silence reading a novel. I was fascinated by Sara’s conversation with her younger sister. They began speaking French so I built up some courage and in French asked them where they were from.

“The Congo.”

“How long have you lived in South Africa?”

“Ten Years.”

“Why did you leave the Congo?”

No answer. They looked at me, stunned. Eventually explained that ten years ago a series of ever shattering events occurred in their home country. They had less access to food supplies, they saw their neighbors and kin targeted by a parable of violence, women were being raped. They were forced to flee and travel 4000 kilometers to this coastal city in South Africa. According to the Human Rights Watch, in 2010 nearly 3000 people were murdered in the Congo, 7,000 women and girls were sexually assaulted and 1 million people fled from the country. My ignorance was Eurocentric–I needed to do more work to understand African politics.

“Do you like living in South Africa?” I asked.

Sara lowly murmured, “I don’t want to answer a question that could be used against me.”

“Fair enough.”

Silence.

There’s no one way to braid Black women’s hair but there is care and diligence and difficulty when the hair is as short as mine. Using a fine comb, the hair has to be portioned in triangular or square patterns. Then the isolated fragment is combed, loosening the entanglements, the locks, the rough texture. Then with two strands of weave each step carefully interlaces the curly strands from one’s scalp until the weave and the hair form one unit.

Nigerians and Congolese migrants work in the same places, live in similar neighborhoods, attend similar churches and provide financial assistance to each other when in need.

With each braid, we began to exchange the stories of our lives as intimate strangers. We discussed the Congolese community in Durban and how they are becoming self-reliant within a sea of xenophobic attacks in South Africa. According to Sara and her sister, Nigerians and Congolese migrants work in the same places, live in similar neighborhoods, attend similar churches and provide financial assistance to each other when in need.

“We have to defend ourselves.”

This Black hair salon allowed us to speak to each other as progenies of different migrants—one within the African continent and one from outside the African continent. We bore the marks of Black people who survived French trans-Atlantic slavery and Belgian colonialism. Yet, our distinct pathways concerning travel and migration spoke to a new set of divisions that gestured towards class and cultural differences—strangeness and familiarity. There is a sense that we are all Black, with our tightly curled hair pressed against our head, high cheekbones, melanin-rich skin, echoing features from Nina Simone to Assata Shakur. Yet, it would not be fair to stick to these aspects alone. We spoke different languages, were accustomed to different foods and carried different passports. Other than the process of getting my hair braided, French and English the colonial links that gave us the space to communicate.

When I asked what they enjoyed about their job, they said that it gave them the chance to make others feel beautiful. Black hair braiders are an integral part of the central business district in Durban. Whether someone sets up a salon or has a small chair on the sidewalk, the people (mostly women and gay men) are accompanied by cassava dealers, electronic goods vendor, a panoply of spices, ripe fruit moldering in the sun, and bright cloth truncated for a tailor.

Black hair salons are microcosms of care that not only function as sites for hair grooming regimes but they become a space for care. Here, we trust our brethren to talk about our abortions, our badass children, and our infidel partners. Black hair stylists function as personal curators. On the surface, it seems like a simplistic client patron relationship, but it is more. This is a place that is part of a confluence for proverbial connections, an opportunity for cultural exchange, it is about knowing and unknowing.

2 in 1 Salon, Joe Slovo Park, Cape Town, South Africa – via Wikimedia commons

Nonetheless, hair care is therapeutic and it can be a place to alleviate the mental stress that Black people bear. Afiya Mbilishaka coined the term, “PsychoHairapy” referring to the way that traditional African spiritual systems provide culturally relevant relationships that promote healthy practices. This gives clients and patrons the space to bear one’s emotional troubles: the salon accommodates expositional stream of consciousness, with little judgment.

This encounter of being both familiar and strange, was one of the many tense moments during my first-time journey to sub-Saharan Africa

Near the end of my hair braiding session, my partner arrived, exciting the attention of the women. He was a white man that entered the space, challenging the racial categories that they had come to know. One woman offered him a ripe, nearly spoiled mango. He politely accepted, yet, later regretted this decision since the mango fibers would spend hours stuck between his teeth. When Sara was done with the last strand, she curled the ends of my hair, oiled my scalp, and took a picture for her records.

Very few people can contest the racial divisions in South Africa, yet, entering into the Black hair salon offered a new way for me to see and connect with other members of the African diaspora. This encounter of being both familiar and strange, was one of the many tense moments during my first-time journey to sub-Saharan Africa. My trip to this Black hair salon in central Durban was a multiethnic mélange of different strands of the African diaspora assembling in a nearly empty space where curly hair was conciliate in a semi-public intimate room. Hair braiders take stylistic risks with the instructions of their clients, deploying confidence where there had been none.

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.””

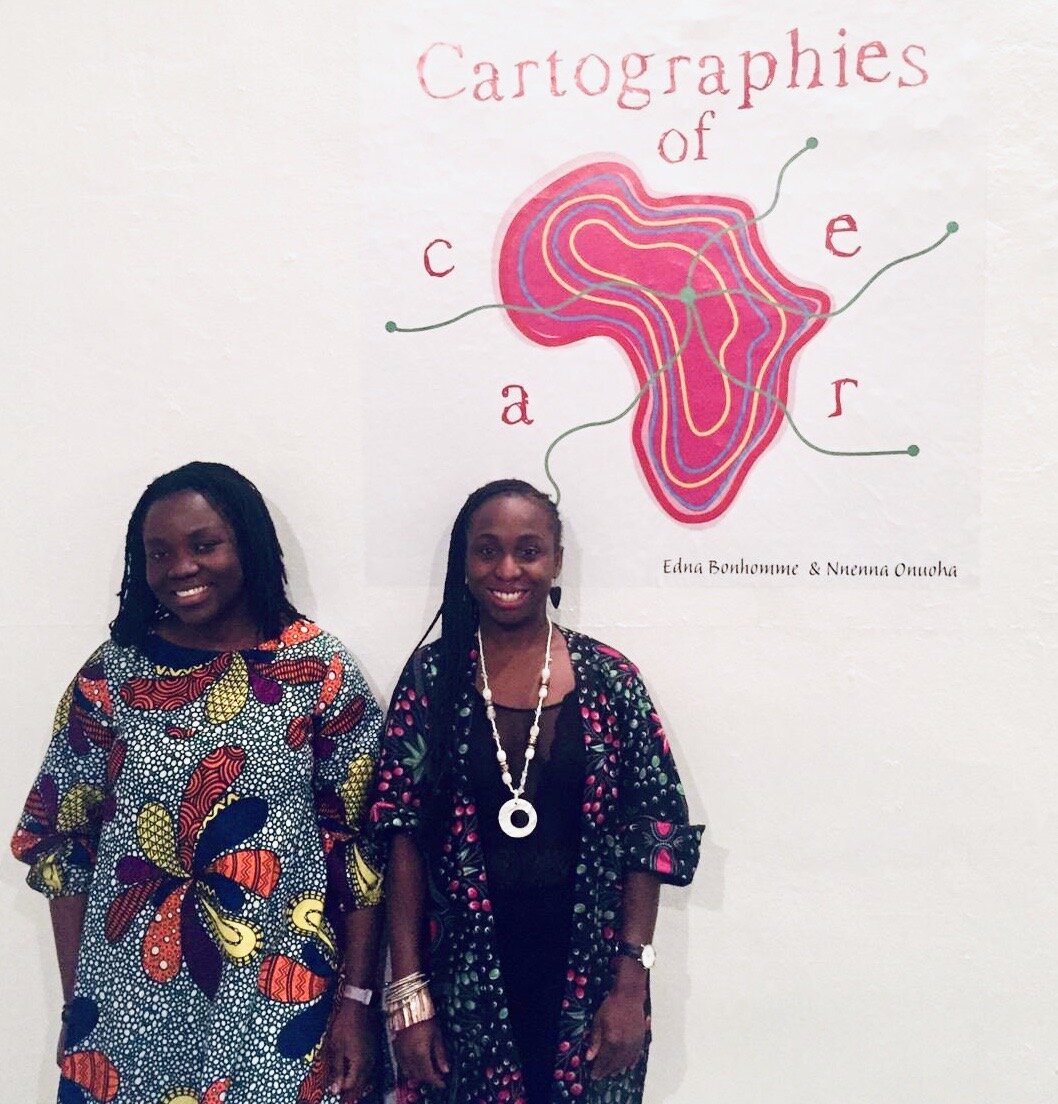

Cartographies of Care Exhibition

The exhibition Cartographies of Care by Nnenna Onuoha and myself, which opens during Black History/Futures Month, charts not only Black Berliners’ often-difficult experiences with the German healthcare system, but also how they find solace and restoration in Afrodiasporic healing arts.

Care is at the core of Black, queer and feminist traditions. Care is ubiquitous, and its parameters dictate how we move through the world; determining whether we survive or thrive. Cartographies of Care traces how healing is imagined and exercised in African diasporic bodies. It gathers experiences and practices from a variety of cultures living in Berlin. These rituals generate modalities of healing that overcome ongoing traumas faced by Black womxn, non-binary, and transgender people who are all threatened by the climate crisis, health inequities, and the rise of the far right. This exhibition is a space of experimentation that works through ancestral memories, mobile archives, and Black futures. It is an invitation for a collective sensorial experience that shows how Afrodiasporic people repair.\

This work began with my ongoing anxieties around practitioners that do not acknowledge my pain interspersed with my desire to find alternative modes of healing. I will say is that Black history month is not just about acknowledging Black excellence from the exceptional but about appreciating the African descended folks that we know in real life, the ones who break bread with us, the ones who laugh with us, and the ones who trust us.

The exhibition can be viewed at alpha nova galeria futura until 13 March 2020.

These are some highlights from on the opening on 14 February 2020. Photographs by Ceren Saner.

Brave Futures: Daddy Magazine Berlin links up with Open Television

Hi friends! DADDY Magazine Berlin & OTV - Open Television have teamed up for #BraveFutures Berlin, a short film race that will take place between February 15 and 17. Everyone who is based in Berlin is invited to participate and we'll prioritise films that were submitted by PoC, LGBTQI, and female filmmakers, creatives, and storytellers. Please don't be deterred if you're lacking experience or don't have the necessary equipment. One of the winning films in #BraveFutures Joburg was filmed by teenagers on an old iphone during a power cut. Films submitted by the deadline will be screened on the 25th and 26th of February for a chance to win cash prizes and 1-year distribution deals with OTV. Good luck! 🖤🖤🖤

Please check out Daddy Magazine!